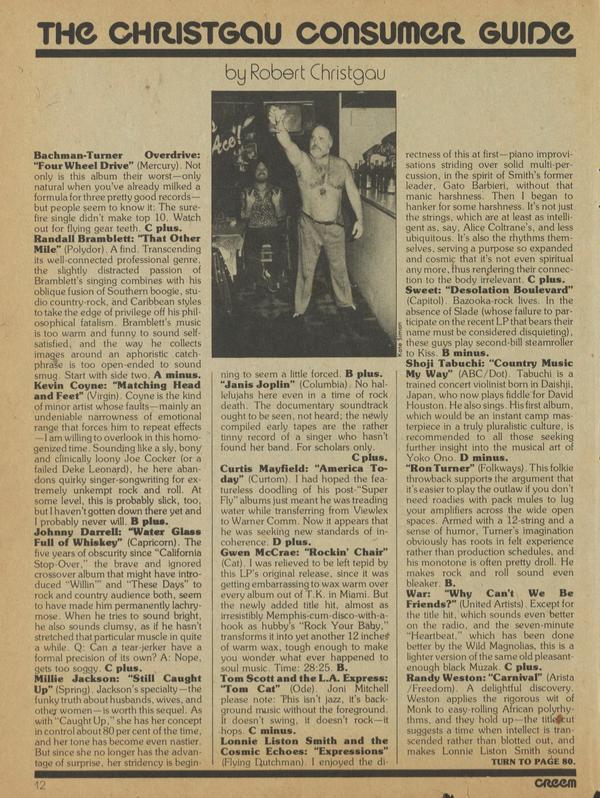

LITTLE EGYPT FROM ASBURY PARK

And Bruce Springsteen don’t crawl on his belly, neither.

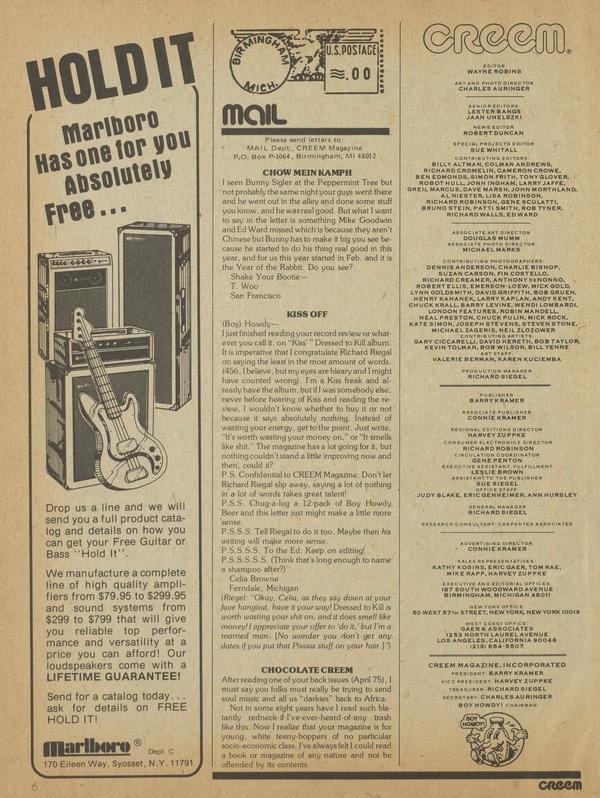

Bruce Springsteen sits cross-legged on his half-made bed, and surveys the scene. Records are strewn across the room, singles mostly, intermixed with empty Pepsi bottles, a motley of underwear, socks and jeans, half-read and half-written letters, an assortment of tapes, and a copy of Richard Williams" Out of His Head, the biography of Phil Spector. The space is small, but Bruce and the two friends listening to Harold Dorman's "Mountain of Love" don't mind. They'ie listening for the final few bars of "Mountain," in which the drummer collapses and loses the beat—the song slows down to a noticeably improper tempo, and the effect is nothing less than absurd. Unfortunately, Springsteen, unlubricated by anything more than the spirit of the thing, is having trouble getting the turntable to spin consistently. (One of those weird things with the green push button that lights up when you press it.) When he finally does, it turns out the record was warped. It is unplayable. Hyster-_ ically, Springsteen sweeps it under the mass of accumulated debris.

"Here," he says, "I'll play ya something else." He puts on a tape of he and the E Street Bapd at the Main Point in Philadelphia. Suddenly, out of the speakers booms his own voice, carcking up at what he's singing. ("That song has some of the best lines," he says shaking his head, "and some of the dumbest") "Stan-din" on a mountain lookin" down at the city, the way I feel t'nite is a dawgawn pity." When the band comes in, the room is charged. The playing and the singing is rough, even ragged, but it is alive, sparked with the discovery of something vital in an old, trashy song. It has been a long time since I heard anyone get this interested in rock and roll, even classic old rock and roll. It has been a lot longer since anyone has gotten me so interested.